In the mid-fifties, Brazilian cinema found itself in a very delicate situation: despite all the efforts and investments made in the past, it was not able to develop and was threatened with extinction by lack of will and creativity. Salvation came from Europe.

Cinema Novo, a new breath in Brazil

More precisely salvation came from Italy, then from France, two countries known for their love of film. In the ruined and devastated Italy of the immediate post-war years, filmmakers had to contend with what they had, or rather what they did not have: extremely tight budgets and no studios to shoot in.

Above all, their aim was to describe the hard life of people trying to regain their footing after dark years, they placed their cameras in the street and filmed quickly by the light of day. Rossellini, De Sica, Visconti were the then new protagonists of a liberated cinema that broke the existing codes.

Their films are screened successfully around the world, and Brazil is no exception.

Italy setting an example for Brazilian Novo Cinema

If Roberto Rossellini’s “Rome, open city” can be considered as the founding act of Italian neorealism in 1945, ten years later Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Rio, 40 Graus (Rio, 40°) is that of Brazilian cinema Novo.

Like his colleague Alex Viany, Dos Santos has learned the Italian lesson: it is necessary to describe daily life in the cities of Brazil as simply as possible and without pretence. This is achievable through a direct cinematographic language, free from verbosity.

Shot in natural settings with non-professional actors, Rio, 40 Graus shows nothing only the occupations of five small peanut sellers in the favelas of Rio.

This uncompromising description of Brazilian reality obviously led to political positions that would only encourage the dark times to come.

The influence of Cannes

The second shock that boosted Cinema Novo took place in the late fifties in France. Godard, Chabrol, Rivette and Truffaut received the prize at Cannes 1959 with Les 400 coups and this became an emblematic film of the new French wave. Here again, Brazilian filmmakers found a new source of inspiration.

Cinema Novo was in fact a mixture of Italian neo-realism and French new wave, the two genres that rejected the exhausted themes of old cinema and who produced works more in touch with real life. Paradoxically, the first Brazilian films to receive international recognition were shunned by the directors of Cinema Novo.

At Cannes in 1962, O pagador de promesas by Anselmo Duarte, did not win the approval of critics and Brazilian filmmakers who criticized him mainly for not concentrating more on the problems of the city. The film was voluntarily located in the countryside.

“O pagador de promesas” finally propelled Brazil to the front of the world art scene, even if it was not really part of the Cinema Novo that the Brazilians would have liked to have made known to the world.

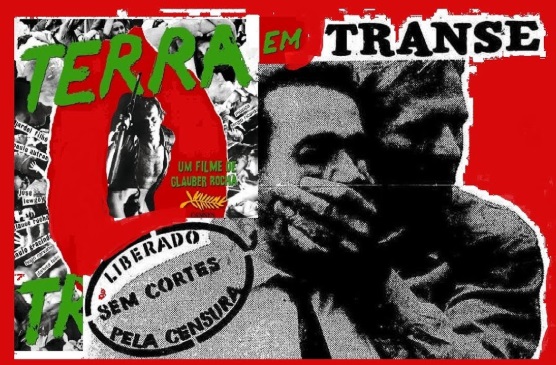

When in 1967 the Bahian Glauber Rocha won the international critics award in Cannes with Terra em Transe (Earth in a trance), and that of staging in 1969 with Antonio Das Mortes, the followers of Cinema Novo could finally enjoy the moment: their most loyal representative was finally recognized by their international peers.

The problem then, was that Brazil was hit by a political bombshell and the film-makers, like the artists in general, had the choice between producing works which attracted the good graces of those in power, or to try to express themselves freely, outside of Brazil, which is what Glauber Rocha did in 1971.

In the shadow of the junta

In 1964, a military coup led by Marshal Castelo Branco overthrew João Goulart’s presidency, and a dictatorship backed by the United States and the CIA would kept the country in a state of tension and repression. This would only relax slightly around the mid-seventies, before a return to democracy in 1985.

For filmmakers who had chosen to stay in the country, the problem with openly engaging their work with certain ideals was no more. While some opted for material totally devoid of political motives, others used masked allegory to express their ideas, like Nelson dos Santos. Then there were those who chose to make completely experimental films, like Rogério Sganzerla, or Júlio Bressane.

The underground cinema or “Udigrudi” broke even more norms than novo cinema did and rallied all those who were against military control of the country. Paradoxically, it was from this power that welcome help would come.

Desiring to control the means of expression that is the cinema, but aware that it cannot survive without help, the government created the “Embrafilme” (Brazilian Film Company) to finance local production.

Reusing the old pre-war recipes, it also taxed all foreign films entering Brazilian territory. In a rather funny way, the subsidies would often go to the filmmakers who formerly claimed Cinema Novo in the seventies.

These years would however bring Brazilian cinema to a new existential crisis: the cinema auteur is no longer commonplace, being replaced by the insipid “pornochanchadas”, soft erotic comedies little subject to censorship since completely devoid of potentially subversive political statements, or in a diametrically opposite style, by movies for children.

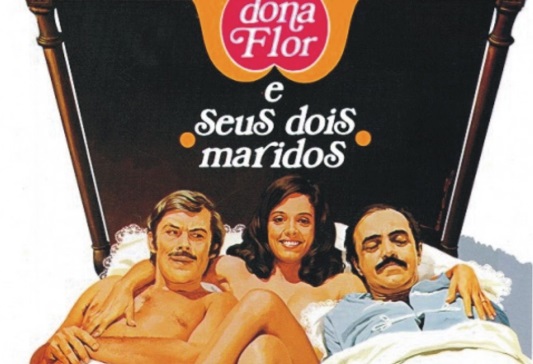

Despite some nuggets like Dona Flor e seus dois maridos (Dona Flor and her two husbands) in 1976, by Bruno Barreto, or Pixote – A lei do mais fraco (Pixote, the law of the weakest) in 1981, by Hector Babenco, the situation became critical for Brazilian cinema, which was now struggling to find a public hit because of the economic crisis and the fact that the public preferred to follow “novelas” (soap operas) on television. The cinemas broadcast less and less Brazilian films and the directors turned to short films in which they gleaned some recognition. A new era is upon us.