Forró is a Brazilian musical style native to the Northeast, it accompanies the popular dance (also named Forró) that now ignites dancehalls across the whole of Brazil and increasingly the world.

Considered for a long time as an obsolete rural folklore, this ballroom music carries with it the poetic nostalgia of a regional life plagued by droughts.

Forró: the joyous lament of rural workers

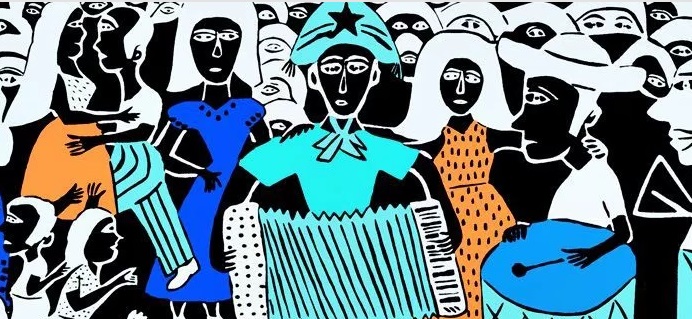

A cross between Indian percussion and Portuguese popular music, forró was first established in the Northeast of Brazil, in the dry and poor states of Sertão. This cheerful and alert music is based essentially on the zabumba (flat bass drum) combined with the accordion and the triangle, two European instruments found in the “corridinhos”, the playful dances of the Algarve, in southern Portugal.

Accompanying the festivities of St. John since the nineteenth century, forró is a lively music that naturally invites one to dance. But not only to dance! The songs speak of love, sometimes rather crudely, but especially of this land of Sertão, poor and cracked by the scorching sun of Nordeste. As much as samba and bossa nova express the typical pleasures of the south of Brazil, equally forró expresses the pains and the difficulties related to this disadvantaged region of Brazil.

The Nordeste has always developed a particularism linked to an old state-nation dream, more or less independent of the rest of the country, and has therefore logically pushed forward its “own” music. Forró has not been confined to the boundaries of Sertaõ: it has traveled with workers fleeing the misery of the North and looking for better fortune to the sites of the mega cities of the South, Brasilia, Rio and São Paulo. Thanks to these exiled Northeast workers, forró lost little by little its reputation of a rural music, seducing the urban populations enchanted by this sensual couples dance.

Forró, the songs of the migrants of Nordeste

Forró is the cousin of the poetry style of the “repentistas”, who were singers of laments who roamed the Northeast to improvise verses accompanied by a viola-guitar with seven metallic strings. Forró is a social criticism as well as ball dance music, with its amorous ironies, its salacious words and its suggestive gestures. The texts often speak of the ferocious struggles between the bandits of honor, the “congaceiros” and the big landowners, the “coroneis”. In short, stories of “Nordic cowboys”, which will serve as inspiration to the filmmakers of the new wave of Cinema Novo. Some films, such as Rui Guerra’s Rifles, will become major works and will participate in the spread of forró beyond the borders of Brazil.

Forró’s most iconic song, Asa Branca, talks all about this. Composed by Humberto Texeira (who would become a politician) and Luiz Gonzaga, it describes the difficulty of life in the Sertão scorched by the sun: “What fire, what furnace / Not a planting foot / For lack of water / I lost my flock … “sang Luis Gonzaga, in” Asa Branca “, a nostalgic anthem of the uprooted.

Luiz Gonzaga was at the origin of “baião”, a dance music with melodies inherited from the medieval songs transmitted by the troubadours of Galicia in the 13th century. Baião was dethroned in the sixties by the triumphant bossa nova, but Gonzaga had already ensured its eternal popularity throughout the country thanks to this song released in 1947.

Asa Branca was considered by many as a sort of Nordeste anthem, and when Luiz Gonzaga died in 1989, his death was so badly felt that three days of mourning were decreed.

Forró today

After being eclipsed by the new musical forms in vogue, forró returned to the edge of the 2000s as a festive alternative to the samba of Rio. The dance steps, two steps to the left, two steps to the right, of the original forró, were doubled in the 90’s to create “forró universitario”. More choreographed and influenced by lambada and salsa, this forró was joined by more modern instruments thanks to groups like Falamansa or Rastapé.

Although the traditional forró has for some years been replaced in the hearts of many Brazilians by its variant, the Sertaneja, it remains alive, especially in the Nordeste during religious or pagan festivals. In the 2000s, the appearance of forró electrônico, with the introduction of modern electronic instruments, gave new impetus to this music with new artists, such as Luan Santana or Simone & Simaria.

In Europe, forró also has its “smugglers”: knowing Brazil very well, Bernard Lavilliers used the accordion and the triangle for his song Sertão, and the Toulouse group Fabulous Trobadors regularly relied on the sounds of the Nordeste for their songs, thus making a more or less conscious connection with their Galician ancestors of the Middle Ages mentioned above. Furthermore, forró has reached the borders of the USA, popular in cities with high cultural diversity such as Boston, this is evident given the high volume of forró classes and dance events occurring there.

Forró nevertheless remains a music rooted in the history of Brazil, and world-renowned artists such as Caetano Veloso or Gilberto Gil owe a debt to this genre. Wasn’t “Mr. Minister” Gil an accordionist in his youth before becoming the guitarist that we all know?